The story of how they had taken on a superpower and, unbelievably, defeated it, appeared to the Greeks themselves the most astounding achievement of all time. And yet somehow, astonishingly, against the largest expeditionary force ever assembled, the Greeks held out. With the Persian King resolved to pacify once and for all the fractious and peculiar people on the western margin of his great empire, the result seemed to most a foregone conclusion. Even the two leading Greek powers, the nascent democracy of Athens and the sternly militarized state of Sparta, appeared ill-equipped to put up an effective resistance. Set against this unprecedented juggernaut, the Greeks were few in numbers and hopelessly divided. Europe was not to witness another invasion force to rival his until World War II and the summer of D-Day. The resources at his disposal were so stupefying as to appear virtually limitless.

As a result of his predecessors’ triumphs, Xerxes had ruled as the most powerful man on the planet. Victory-rapid, spectacular victory-had for decades seemed to be their birthright. Military adventures of this kind had long been a speciality of the Persian people.

In 480 BC, some forty years before Herodotus began his history, Xerxes, the King of Persia, had led an invasion of Greece.

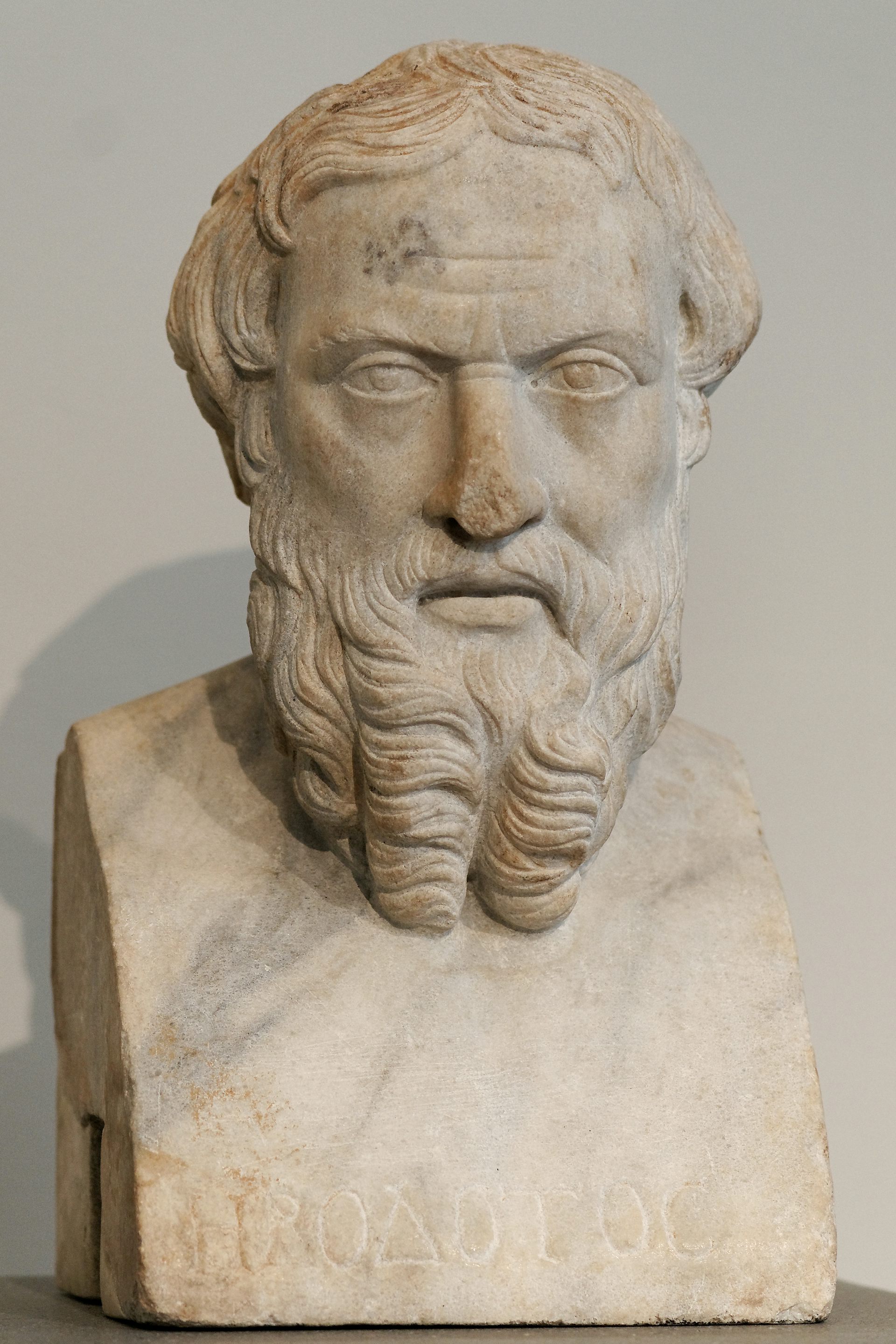

Difference had bred suspicion-and suspicion had bred war.Ī war like no other. These, at least, had been made all too recently and tragically clear. Yet if the origins of the conflict between East and West appeared lost in myth, then not so its effects. Perhaps the kidnapping of a princess or two by Greek pirates had been to blame? Or the burning of Troy? “That, at any rate, is what many nations of Asia argue-but who can say for sure if they are right?” As Herodotus well knew, the world was an infinite place, and one man’s truth might easily be another man’s lie. Asiatics, so Herodotus reported, “believe that the Greeks will always be their enemies.” But why they should have come to this conclusion in the first place was, he acknowledged, a puzzle. His goal was to explain what would now be termed “the clash of civilizations,” the inability of the peoples of East and West to live together in peace. In around 440 BC, some three centuries after Homer, singing the wrath of Achilles, composed the Iliad, a Greek by the name of Herodotus embarked upon a project no less epic.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)